There is an overwhelming consensus that the campaign for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections compared to the previous two was a more humdrum affair—issues that could raise the emotive quotient nationally were missing. This sentiment was reflected in the results declared on June 4, with most states not having one clear winner, but different ones. There is no single overarching factor that can explain all of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) setbacks in this election and the gains made by the INDIA bloc, especially the Congress party.

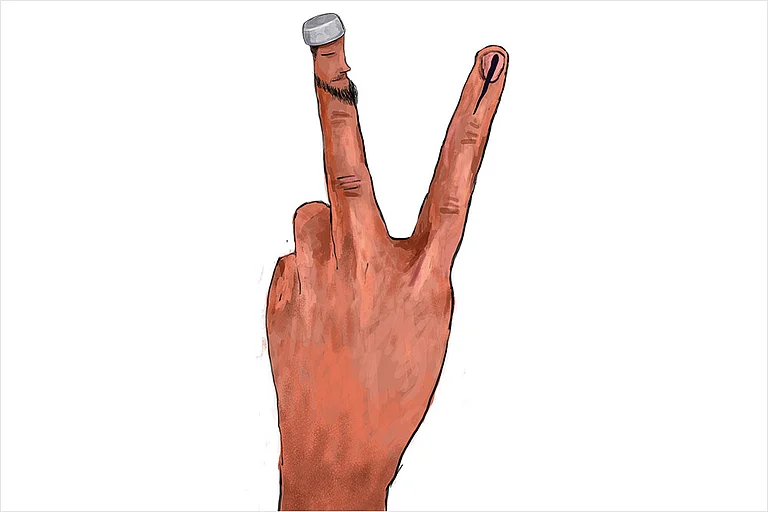

Lok Sabha Election 2024: Return Of The Ideological Divide

The 2024 election campaign highlighted the ideological divide at the heart of Indian politics

However, despite the consensus that state-level dynamics played a greater role in shaping the verdict, the 2024 election campaign also highlighted the ideological divide at the heart of Indian politics. Comparing the campaign narrative of the Congress party and the BJP, political scientist Suhas Palshikar wrote: “The two registers are speaking about two very different ideas of India.” And, the leaders of India’s two main national parties, Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi, were the principal interlocutors of the two contrasting ideological images.

Ideology and Voter Mobilisation

The two very different ideas of India, as Pradeep Chhibber and I have outlined in Ideology and Identity: The Changing Party Systems of India, are rooted in the process of state formation in India that involved two simultaneous challenges of regulating social norms and redistributing property (the politics of statism) and giving marginalised castes, which had faced significant discrimination, their just place in the state-building process (the politics of recognition).

The BJP, under PM Modi, consolidated the social and economic ‘right,’ that is, citizens who do not want the state intervening in social norms, redistributing property, recognising religious minorities, and equating democracy with majoritarian values. The BJP benefitted from the structural changes in Indian society, which created an urban middle class that leans right on social and economic issues.

This vision is opposed by many parties on the Centre-Left, including the Congress party. During the Nehru years, the Congress party began as an umbrella coalition representing those from the Left and Right. The main opposition to the Congress in the 1950s and 1960s came from the socialists. Indira Gandhi’s ascension to power changed India’s electoral landscape. She centred the state as the solution to economic inequalities in India, nationalised financial institutions, and banned corporate donations.

With the failure of the state-led development model in the 1990s, the Congress party became bereft of any deep ideological commitment, reflected in the narrowing of its social base. Rahul Gandhi, in the past two years with the two Bharat Jodo Yatras, and the 2024 campaign, has made efforts to stake out a clearer vision for the Congress, a vision based on economic and social justice that opposes the BJP’s ideology.

Ideological Issues in 2024

The Congress campaign in 2024 focused on counting castes and religions to provide social and economic justice, with some undertones of the redistribution of wealth. The BJP argued sharply against any idea of redistributing wealth or pursuing a caste census as a means of providing social justice while simultaneously attacking the Congress platforms as coloured in religious overtones, sharpening the Hindu-Muslim divide.

Why did the 2024 elections witness sharper polarisation on ideological axes compared to the previous two elections? The routine ideological platforms sometimes can gain greater salience in a normal election than in a critical one. These two types of elections differ in multiple ways, but more importantly, the social basis of political power gets realigned in a critical election. This means that the party which eventually comes out on top after winning the critical election manages to add a significant number of new voters to its base. These new voters comprise those who have voted for other parties in the past, and also those who were hitherto not mobilised in the electoral arena.

The 2014 Lok Sabha elections were critical in that sense, and 2019 consolidated the patterns of the BJP’s national dominance. The 2014 elections contained a profound anti-incumbency sentiment, reflected in public opinion surveys capturing greater dissatisfaction with the incumbent UPA government’s performance.

In the aftermath of Pulwama and Balakot, the national security pitch drove the 2019 election campaign. The ‘rally around the flag’ effect was visible in that the everyday economic issues lost their salience among many voters, who viewed bread-and-butter issues through the lens of nationalism.

The BJP in these two elections transformed as a political party from a limited social base among upper castes, middle classes, and urban voters to a broader base representative of Hindu society. The Congress, on the other hand, shrank both geographically as well as socially.

Increasing Polarisation?

Some have argued that the combined effect of economic anxieties at the bottom of the social pyramid, and the counter-offensive of the Opposition’s “samvidhaan khatre mein hai” against the BJP’s clarion call of “abki baar 400 paar” played an important role in shaping the election outcome. The former may have led a sizeable section of the non-general castes to believe that they may lose their reservation status.

While it may not be easy to quantify the effect of these narratives on the final outcome, the outsized role leaders such as Modi and Gandhi played in shaping their party platforms indicates their role as representatives of particular ideologies. Through their speeches and actions, they inspire the core voters to become vote mobilisers for the party, a fence-sitter to move closer to their party and enthuse a larger swathe of the population to participate in the electoral arena.

The articulation of the respective party platforms by these two leaders, in some ways, has led to the hardening of ideological stances in recent years. While it is natural that there will be areas of disagreement between the two ideological camps, the success of Indian democracy is contingent on both sides extending the maximum possible cooperation to find political solutions to emerging problems. And a developing country like India has plenty of such problems. Accommodating the aspirations of millions of young Indians is contingent upon the realisation that the emerging ideological fractures are likely to engulf everyone involved.

Should we expect a moderation in ideological stances of both camps from here on? It has become evidently clear from the 2024 election campaign that the increasing political polarisation has led to an irreversible trust deficit between political parties, and, in turn, putting democratic norms and informal power-sharing arrangements under deep strain. Both sides feel that they are under siege.

Advertisement

The BJP believes that the Opposition (Khan-Market cabal in its lingo) continuously schemes and attacks it, while the Opposition is convinced that the BJP has used all the might of the state machinery to squeeze it further. The resultant effect has been that the formal and informal mechanisms of power-sharing have completely broken down. And the object of political discourse is now reduced to delegitimising your political opponent. Both sides have now resorted to creating a web of misinformation and frequently indulge in whataboutery.

Can the compulsions of a coalitional arrangement at the centre necessitated by verdict 2024 help in minimising the ideological distance and trust deficit? While it would be tempting, and perhaps desirable, to argue that India urgently needs a bi-partisan consensus on solution to its present and future challenges, the signals from both camps post-verdict suggest that ideological divide is only likely to get widened in the coming years.

Advertisement

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'Return Of Ideology')

Rahul Verma is Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research (CPR), New Delhi

-

Previous Story

Trouble For Siddaramaiah As Karnataka Governor Gives Nod To Prosecute CM In MUDA Scam

Trouble For Siddaramaiah As Karnataka Governor Gives Nod To Prosecute CM In MUDA Scam - Next Story