It is interesting that some of Sanskrit’s most celebrated works of romance explore the pain of separated lovers. Not just that, the aesthetic emotion of viraha is almost more exalted than shringara—the complementary emotion of ‘love in union’. Surely, there’s more than a hint in there about how we view love and whether we think a long, happy and fulfilled love is possible.

Poems Of Pain Always Scored Over Songs Of Lust In Classical India

Did classical Indian literature focus more on the absentee lover than on the joys of union, probes Arshia Sattar

One of the most romantic moments we got in the classical Sanskrit literary tradition was from Kalidasa. The dramatist’s Meghaduta has an exiled yaksha sending a message to his beloved via a raincloud. Replete with all that Kalidasa does best, the lyric poem abounds in pathetic fallacy, where each and every aspect of nature reflects the yaksha’s yearning. Monsoon exacerbates that urge. For, it’s the season of love, when men return to their homes from faraway lands, from their work as soldiers and traders and as farmers at a time when thirsty fields are left to soak up the rains. J.C. Holcombe translates: “In wind, which off the River Shiprá brims/With smell of morning lotuses, is caught/The long, sad calling of the cranes, at which/The coaxing lovers skillfully exhort/Again their pleasure out of tired limbs”.

In the Valmiki Ramayana, dominated by the separation of its central characters, the most exquisite poetry in the text is provoked by Sita’s absence. In fact, Valm-iki is moved to create a new poetic meter, when he sees the grief of a bird who cries out for the loss of his mate. One might be tempted to suggest that viraha itself is the rasa of the story. Observe Rama’s grief in the rainy season while he is waiting for Sugriva to keep his promise to search for Sita. “The rainy season has begun…. The sky is like a pining lover, the gentle breeze his sighs, the evening clouds the sandal paste on his chest, the white clouds the pallor of his face…. The sky, struck by lightning’s golden whip, cries out in pain in a rumble of thunder. And the lightning flashing across the dark clouds make me think of Sita writhing in Ravana’s dark arms.”

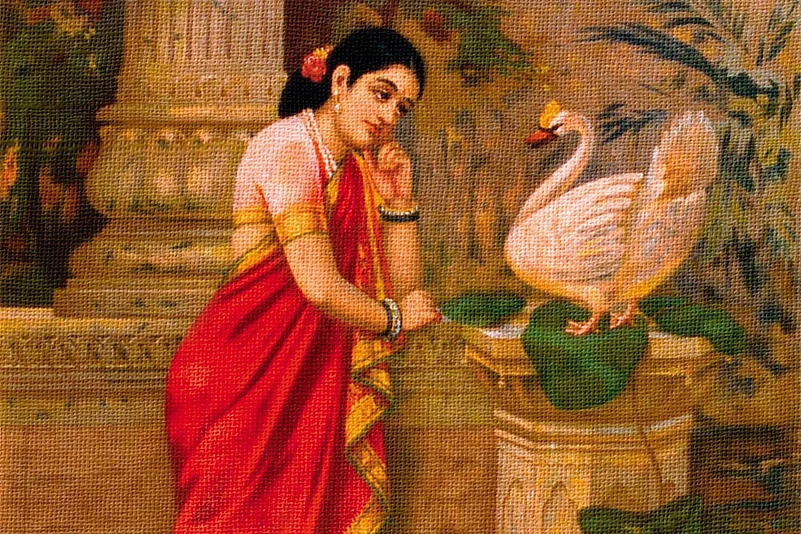

Do we find in our ancient stories and poems true romance at all? Or a calm and stable love that can be enjoyed together? The Kama Sutra, touted as a manual of love, actually speaks more of seduction than of love or romance. Other literary genres have stories of romance and love, every now and then. Certainly, the story of Nala and Damayanti has elements of sweet romance as a golden swan carries messages of love and longing between the two courting lovers. Further, their love triumphs over the deceits of the gods who attend Damayanti’s swayamvara—she is able to identify the true Nala simply because of her love for him. Savitri and Satyavan, too, battle the odds—fatal curses and even Yama himself—so that they can live long and happily together. There is also the magnificent, if macabre, myth of Shiva and Sati and their adoration for each other. Sati marries Shiva against the wishes of her father, Daksha. One day, Daksha organises a grand sacrifice and invites everyone except the couple. Sati storms into the enclosure and denounces her father for insulting her husband. Her anger is so great that she sets herself on fire. Shiva hears of this and is distraught. He claims Sati’s charred body and, carrying it on his shoulders, begins the dance of world destruction. At this, Sati’s body breaks into pieces (sometimes, Vishnu dismembers the body in order to calm Shiva) and falls to the Earth, creating shakti pithas where the female energy is worshipped in a chain of temples that dot the Indian subcontinent.

We never read this myth with its towering and destructive passions as a love story—its popular significance tends to be in terms either of Shiva’s wrath and the origins of the tandava, or in terms of Sati’s devotion to her husband. Recognising? Shiva’s mad grief at his wife’s death as born from love would change the story’s meaning entirely, taking it out of the realm of cosmogonic myth and bringing it closer to us, to our own experience of love and loss and grief. So also, if we choose to read the Ramayana as a love story, albeit another tragic one, Rama comes to us as someone whose emotions of despair, anger, fear and suspicion are familiar. We may not sympathise with his reactions to these emotions, but we have the chance to think of this man-god as someone more like ourselves than not.

Sanskrit court poetry, with its many adornments and flourishes, revels in the idea of romance as well as physical love much like they are with the delicate but highly evocative Sangam poetry in Tamil. Whispered sweetness, shy confusions, nail-marks on breasts and jingling waist girdles speak of the joys of love in union, but there are an equal number of bangles slipping from pale, thin wrists that tell us that the lover is far away. Ingalls translates from Sanskrit and tells us “Beautiful is the nailmark shaped like a crescent moon/upon the circle of your breast:/a ship of Love in which to cross/the waves that are your triple fold”.

A.K. Ramanujan translates thus from the Tamil Kuruntokai collection: “Bless you, my heart/The shell bangles slip/from my wasting hands./My eyes, sleepless for days,/are muddied./Get up, let’s go, let’s get out/of this loneliness here./Let’s go/where the tribes wear/the narcotic wreaths of cannabis/beyond the land of Katti,/the chieftain with many spears,/let’s go, I say,/to where my man is,/enduring even/alien languages.”

The stony existence of Ahalya, separated from her husband for eons, ends after a Rama touch

Prakrit poems, too, carry these images and landscapes of love, but they are more mischievous: they bring to our notice mistresses and lovers who are not husbands. They more explicitly add a delicious layer of love outside marriage, both men and women seeking these illicit pleasures and, for the most part, getting away with their extra-marital relations. Here’s one of my favorites from Arvind Krishna Mehro-tra’s translation of the Gathasaptasati. “Mot-her-in-law, one word/About the long bamboo leaves/In my hair, and I’ll bring up/The dirt-marks on your back”. And another. “The wretched night’s dark/My husband’s just left/The house is empty:/Neighbour, stay awake/And save me from theft”.

Along with mistresses, secular Sanskrit texts also celebrate the figure of the courtesan. The Kathasaritsagara in particular often places this glorious woman—beautiful, educated, quick-witted—at the centre of its stories of merchants and traders. If we want to think about a ‘liberated’ woman, the courtesan comes closest, free as she is of the stigma we attach to modern ‘sex workers’. The courtesan has dignity and a special place in society outside the caste system. She is the ganika rather than the veshya.? Although she seems to have stepped out of the pages of the Kama Sutra with her mastery of the arts of seduction, this magical, almost mythical, creature sometimes finds herself in love. This is a disaster: it prevents her from doing her job and earning the living, which supports an entire retinue of servants and musicians. We realise she, too, is trapped as much as any other woman. But for all this love and romance, and sexual desire, what of marriage? What do these and other stories tell us about that? Anusuya and Arundhati are good wives; their virtues enhance the glory of their sage husbands, Atri and Vasishtha. There is Manu’s Dharma Shastra, that highly prescriptive manual for how to live in the world as men and women. But it’s more likely that stories, even magical ones, reflect social realities more than a book of rules. In the stories, let us not be surprised that, as ever, within a marriage, a woman’s fidelity is of supreme importance. One of the more horrifying myths about the consequences of a woman’s stray thought is the one about Jamadagni and Renuka. Because of her virtues as a chaste wife, Renuka had the power to roll water up into a ball and carry it home on her head without the need for a pot. One day, as she leaves the river with her water, she notices the handsomeness of the king of the Gandharvas, who is enjoying himself nearby with his wives. Her ball of water breaks; she reaches home dripping wet. Her husband knows at once that she has thought about another man. He orders his son, who is later known to us as Parashu-rama, to cut off his unchaste mother’s head. Renuka is beheaded by her son, who cannot disobey his father. Jamadagni offers his son a boon for his obedience and the young man asks that his mother’s head be restored to her body.

The Radha-Krishna romance comes into deep focus in Jayadeva’s famed work Gita Govinda

A less physically violent but equally brutal story about the consequences of a wife’s infidelity is the one in which Ahalya, wife of the great sage Gautama, sleeps with Indra, the king of the gods. In some versions, she does this knowing that Indra has taken the form of her husband; in others she is innocent of this deception. But it matters little whether this was a deliberate choice on her part or whether she was fooled—when Gautama finds out what has happened, in all the versions of the story, he curses Indra and his wife. Indra’s curse is easily modified by the gods, but Ahalya is turned to stone (or made formless) until she has the good fortune of being touched by Rama. For her transgression, Gautama destroys her physical body, which is the location of her pleasure—a pleasure she will now never experience again.

It’s not only the truth about a woman’s fidelity that is important; it is also other people’s perception of that fidelity. Witness what happens to Sita on the basis of mere gossip. The Valmiki Ramayana has an interesting account of the story that Bhadra carries to Rama. Here, the townspeople complain that Rama has set an unreasonable standard of behaviour for his citizens by taking his wife back after she had been in the house of another man. So, Rama banishes his wife; his citizens no longer need to rise above themselves and exhibit the same grace as Rama had done. Later versions of this incident are less complex and boil the reasons for Sita’s banishment down to something like ‘the queen must be above reproach’. Ironically, Sita’s ultimate and irrefutable assertion of her innocence lies in her disappearance from the world of humans that leaves her husband bereft.

In the texts and genres—myth, epic, the shastras and the sutras—that are celebrated for demonstrating and upholding the so-called ‘values’ of Hindu culture, women are controlled by the institution of marriage. The expression of any kind of sexual desire by a woman or the suggestion of her multiple sexual partners cannot go unpunished. Shurpanakha, for instance, is mutilated because the demoness dared to speak of her attraction to Rama. Draupadi can be called a whore in front of her elders and stripped of her clothing because she sleeps with more than one man, even though they are her legitimate husbands. There are far fewer instances of men being chastised for their promiscuity. Only Indra is a regular offender in this regard. Rakshasas (notably Ravana) and other demonic beings are cursed because of their aggression towards women, but they never experience the immediate, retributive physical and emotional violence that women who are deemed transgressed do.

Circumstances led Pandava prince Arjuna to dress as a sanyasi and abduct lover Subhadra

On the other hand, when we think of love and romance in an Indian context, no one comes more quickly to mind than Krishna, the irresistible flute player of Vrindavan. Seducing hundreds of gopis, at the same time, as elusive to each as he is present to them, unfaithful, flirtatious and yet, utterly compelling, Krishna is romance itself. But the love that he offers is shadowed by the promise of heartbreak; even his beloved Radha cannot hold him. However, the eternal romance that Krishna represents became possible only when bhakti, ardent devotion and complete surrender to a god of one’s choice, conquered the heart of Hinduism. Bhakti allowed love for the divine to be transgressive, promiscuous and filled with sexual desire—be it Andal’s love for Vishnu or Mira’s for Krishna or Akka Mahadevi’s for Shiva. Particularly in the poetry of the women saints who were ‘mad for god’, human romance and desire were all sublimated into a love for god and found full and free expression. Mira was even able to speak of her true lover in the presence and context of her earthly marriage.

For the classical period, however, we must return to our secular texts to gain some sense of what romance and love and happy marriages might actually have been like. It’s impossible to think there was a time when these gentle human emotions were not important, that men and women lived lives without romance, they married for reasons other than love, they endured relationships that were difficult and unfulfilling. What we need to ask oursel-ves is why the love that humans can and do feel, the kind that elevates both lover and beloved, does not appear in the texts we place at the centre of our culture.

(Arshia Sattar is a translator, facilitator, author and director, having obtained a PhD in South Asian Languages and Civilizati-ons from the University of Chicago. Peng-uin Books has published her abridged translations of the Kathasaritasagara and Valmiki Ramayana.)